My Least Favorite Trend in Pop Music

And its surprising upside

Last Sunday, it was Grammys night in America. For my subterranean readership, the Grammys, affectionately referred to as “music’s biggest night,” serves as an annual event in which the Recording Academy awards songs, albums, and individuals that made some modicum of impact during that eligibility year. As a music fan, the Grammys are like if the entirety of an NFL season took place over the course of three hours and, as a non-football fan, they make me better understand why middle-aged men scream, cry, and even get violent when their team isn’t doing well. That is to say, myself and others have spent many a Grammys Sunday watching in anticipation, hoping the Recording Academy awards our favorite songs, albums, and individuals not just because we think they deserve it, but also so we can then get on social media and gloat about how our faves won the big prize.

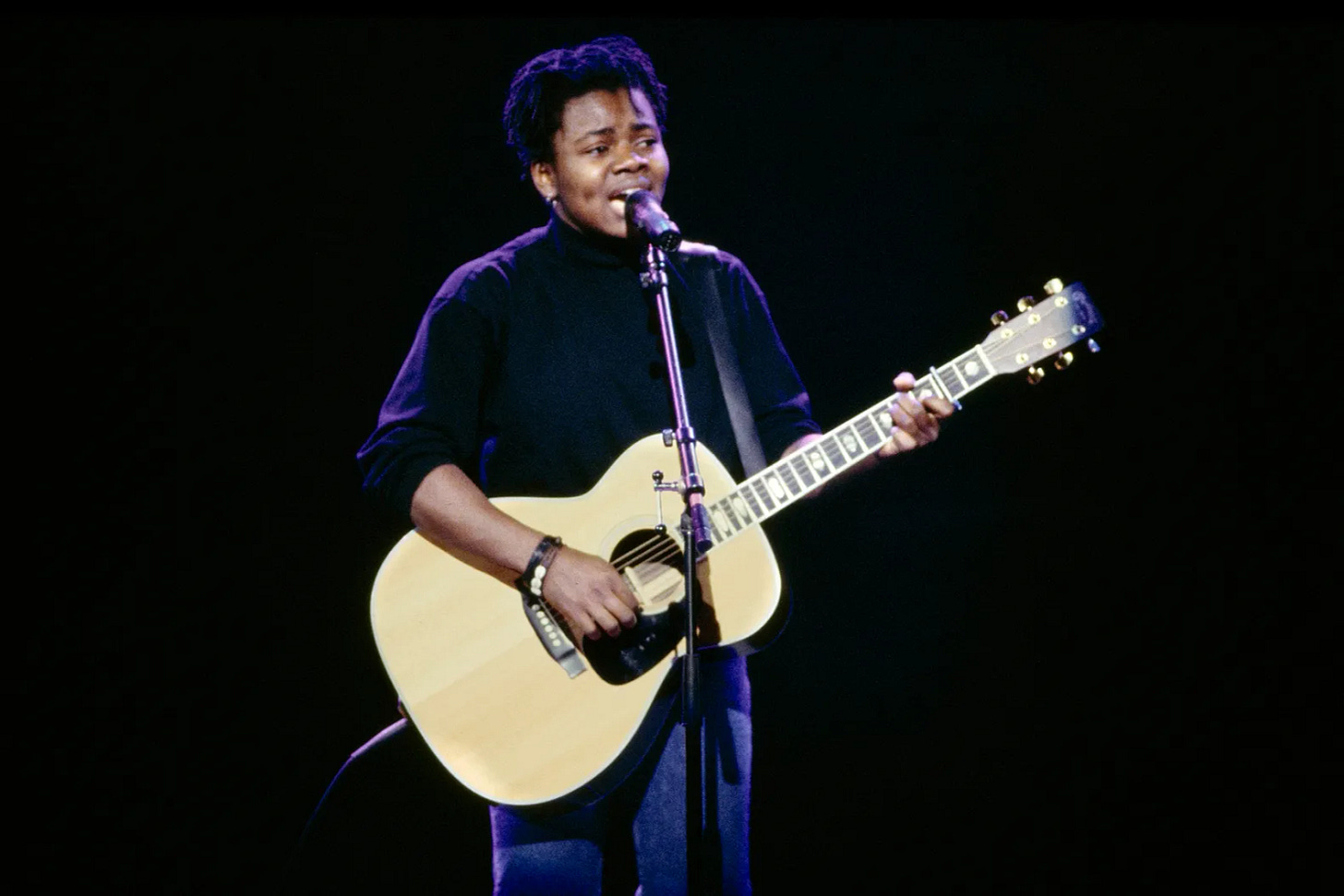

The Grammys, however, are not solely about awards. In fact, the awards really just entice people to watch a broadcast that is, primarily, composed of live musical performances. In a bit of an aberration from years past, the performances that drew the most attention to this year’s ceremony were not those of the youngest new pop stars on the scene. Rather, some of the most talked about performances of the night included Annie Lennox’s tribute to the late Sinéad O’Connor, in which she called for a ceasefire in Israel’s War on Gaza, Joni Mitchell’s captivating performance of “Both Sides Now,” and Tracy Chapman joining Luke Combs for a performance of her 1988 hit, “Fast Car.”

I fell in love with “Fast Car” on a night much like the one wherein I write this letter. That night, I was up late working on an essay in Posvar Hall, which is a lecture hall on my alma mater’s campus (and the largest building on that campus, to give you a fact from my tour guide days). Generally, I like to listen to music while I’m writing. For some reason, that night, I listened to “Fast Car.” I’m sure I’d heard it before then, but something about this time really stuck with me. That iconic riff that starts the song, Chapman’s dulcet tone throughout the record, and lyrics that weave a tale of love, loss, and ultimately acceptance lit my brain up like a switchboard. Immediately after that, I listened to the rest of Chapman’s 1988 album and added “Fast Car” to all applicable playlists. I also did some research into Chapman’s career and immediately understood her as one of the coolest people ever. Not only did she write one of the greatest songs of all time, but she also wrote openly about the impending proletariat revolution, sued Nicki Minaj years before Nicki would try Megan thee Stallion, and even had a romantic relationship with Alice Walker. Why, at twenty years old, was I only just finding out about this legendary figure?

I soon came to understand, though, that me just learning about all of that was very intentional on Chapman’s part. She became famous in a time before social media, when celebrities could afford to give their fans much less access to them. It’s also my sense that, in this time when there was less pressure to be accessible to her fans, Chapman still managed to make herself less available than the typical artist. In an interview from 2002, Chapman remarked:

“I have a public life that’s my work life and I have my personal life… In some ways, the decision to keep the two things separate relates to the work I do. I don’t think I would have anything interesting to write about if I didn’t give myself time to have a life, to hang out with my friends or read a book or travel someplace I’ve always wanted to see.”1

It’s something I really respect about Chapman; she seems dedicated to keeping her career about the art that she creates rather than the discourse she can inspire with her public image. As such, she would probably think it was silly I have such an interest in the fact that, I will repeat, she dated Alice Walker. Chapman’s is a type of fame that we so rarely see in a landscape that is so obsessed with clicks, views, and engagement.

Therefore, it was an understandably big deal when Chapman gave a surprise performance at this year’s Grammys. However, a ceremony celebrating the previous year in music would have been incomplete without the inclusion of “Fast Car.” This is, of course, because of the popularity of country star Luke Combs’ cover of the song, which peaked at number two on the Billboard Hot 100 and is currently in its forty-fifth week on the chart. Writing about Combs’ version for The New York Times, Lindsay Zoladz argues that, “the appeal of Combs’s version… came from how closely it hewed to Chapman’s recording. Combs gave the rhythm section a little more arena-rock oomph and added a slight country twang to his phrasing, but that’s really it.”2 Despite how faithful Combs’ cover remained to the original, there was no question that it outperformed its predecessor on the charts.

As a fan of the song, I do have to admit that I came to resent the success of Combs’ cover. While some of this has to do with my individual taste, it mostly has to do with the fact I, quite simply, did not like the fact that this exceptional song written by a Black, queer woman was now being associated with a white guy. Part of why I came to admire Chapman in the first place is because of all she’s been able to accomplish while being herself. As a queer artist myself, I have been made to feel as though what I have to contribute is too niche, or unrelatable, or unmarketable to be successful. I imagine Chapman was forced to internalize similar sentiments about her own work, along with other ones that were more explicitly tied to her race and her gender. However, because she is a uniquely talented individual, she was still able to rise to the top. As such, I was not only inspired by her impressive body of work but also her success, and she made me believe that something similar was possible for me and my art. Therefore, it opened a bit of a wound to have Combs garner the level of acclaim that he did while enjoying the privilege of being a straight, white man. It legitimized a certain fear that, no matter how hard I or people I admire work, we can be eclipsed because of traits that are ultimately out of our control.

Now, on some level, this is an unfair sentiment to hold against Combs’ cover of the song. Firstly, he had no hand in creating the matrices of hegemonic power that exist over all of us. In addition, as someone who does not know him personally, I cannot know the extent of Combs’ experience on this Earth. However, I know he’s a human being and, thus, has probably experienced his fair share of setbacks and shitty circumstances, and I don’t share my frustrations as a way to minimize them. I’m simply saying that it’s far less likely that those setbacks and shitty circumstances have been tied to his race, or his gender, or his sexuality.

I also wouldn’t write about this if I didn’t identify it as a larger trend in the music industry. That is to say that Chapman’s “Fast Car” is not the only song that I’m aware of that’s received this treatment. Another that comes to mind, especially as a queer person from a Philly sports family, is Robyn’s 2010 classic, “Dancing on my Own.” For two playoff seasons in a row now, I have lived through a Red October which finds Phillies fans belting out this tune whenever the team wins a game. While I love this song, I have to live with the pain of knowing that my fellow fans are not referencing Robyn’s original version, but instead Callum Scott’s 2018 cover. A cover that, in my view, eliminates much of what is special about Robyn’s original and yet, at least in certain audiences, has, like Combs’ cover of “Fast Car,” eclipsed the popularity of its predecessor. There is a bit of a theme emerging here, and it’s not one that I find particularly exciting.

The appearance of this trend is precisely why I became frustrated with that Times piece I quoted earlier. Elsewhere in that article, Zoladz describes the performance as, “a genuine moment of warmth and unity, the sort seldom offered these days by televised award shows — or televised anything, really.”3 While, like Zoladz, I did enjoy the performance, I find that her analysis joins a certain type of pablum around Combs’ cover of the song. One that expresses the importance of “unity” instead of engaging with the systemic elements at play in the music industry that advantage artists like Combs as they simultaneously disadvantage artists like Chapman.

Again, though, I would like to stress that very little of this actually has to do with Combs himself. In fact, I have only been reassured by what I have learned about him since Grammys night. For one, he’s a diehard Tracy Chapman fan. In a segment that played before their performance, Combs can be heard absolutely gushing over Chapman, saying, “Tracy’s such an icon and, I mean, one of the best songwriters that I think any of us will ever be around to see… it’s such a cool, full-circle moment for me. To be associated with her in any way is super humbling for me.”4 Additionally, according to an Entertainment Weekly article5, it seems that he and his team met each of Chapman's demands as they prepared for the performance. To cap it all off, Combs even published a heartfelt tribute to Chapman on Instagram, writing:

“Tracy, I want to send my sincerest thanks to you for allowing me to be a part of your moment. Thank you for the impact you have had on my musical journey, and the musical journeys of countless other singers, songwriters, musicians, and fans alike. I hope you felt how much you mean to the world that night. We were all in awe of you up there and I was just the guy lucky enough to have the best seat in the house.”

It seems that, with this performance, Combs made each and every effort to parlay the success he found with his cover and direct it back towards Chapman, which is a lot more than other artists in his same position may have done.

On top of that, the fact remains that Chapman’s performance was one of the most talked about of the night. If nothing else, it flooded the Internet with posts about her triumphant return and perhaps even earned her a few new fans. Ultimately, one of my wishes for any artist, particularly those I admire, is to have their work recognized and appreciated, and, over the past week, that’s certainly happened for Chapman. Therefore, while I will remain vigilant towards the trend that I have identified, I also have to recognize the potential upside. And who knows? Maybe if the Phillies win the World Series in the next couple of years, Robyn and Callum Scott will come together to perform “Dancing on my Own” somewhere on Broad Street. Much like the success of “Fast Car,” only time will tell.

This week’s recommendations:

This essay on New York’s zoning archaic zoning laws

Your local library

“Baby Can I Hold You” by Tracy Chapman

“A.S.M.R Lover” by RuPaul

“Don’t Forget Me” by Maggie Rogers

This lip sync from RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars season one, which was originally a much bigger part of this essay

M., Aurélie. “2002 - Tracy Chapman Still Introspective?” Tracy Chapman Online, 15 October 2002, Link.

Zoladz, Lindsay. “Tracy Chapman and Luke Combs Gave America a Rare Gift: Harmony.” New York Times, 5 February 2024, Link.

^

Travis, Emily. “How Tracy Chapman and Luke Combs’ moving ‘Fast Car’ Grammys duet happened.“ Entertainment Weekly, 9 February 2024, Link.

^